How did Beethoven Compose Masterpieces in Silence? The Triumph of Genius Over Disability

Discover how Beethoven composed some of his greatest masterpieces after losing his hearing, relying on various techniques, including the extraordinary power of inner hearing.

When we think of Ludwig van Beethoven, we picture a towering genius and one of the greatest composers in history. But perhaps even more astonishing than his music is the story of how he created some of his most celebrated works after losing his hearing. How was it possible for Beethoven to compose masterpieces like the Ninth Symphony and the late string quartets when he could barely hear a note? The answer lies in the extraordinary power of his mind, his relentless determination, and the phenomenon known as “inner hearing.”

The Onset of Deafness

Beethoven first noticed hearing loss in 1798, at age 27, describing symptoms like tinnitus (ringing in the ears) and difficulty hearing high-pitched sounds. By 1801, he confided in friends about his anguish, writing, “I must live like an exile, avoiding all social life.” His 1802 Heiligenstadt Testament—a letter to his brothers never sent—revealed suicidal despair, but also resolve: “I will seize Fate by the throat; it shall not crush me.”

Medical historians speculate his deafness stemmed from otosclerosis (abnormal bone growth in the ear) or auditory nerve degeneration, exacerbated by lead poisoning or typhus. By 1814, conversations required written exchanges in “conversation books,” and by 1824, he could not hear the applause at the premiere of his Ninth Symphony.

Adapting to Silence: Tools and Techniques

How could Beethoven compose some of the world’s most enduring music without the ability to hear it? The answer lies in his extraordinary mastery of “inner hearing,” or audiation: the mental ability to imagine and manipulate music entirely within the mind. Years of rigorous training, relentless study of scores, and deep analysis of musical forms had given Beethoven an internal soundscape so vivid that he could “hear” every note, harmony, and rhythm as clearly as if they were being played aloud. This was not just a vague sense of melody; Beethoven could mentally audition different themes, experiment with harmonies, and shape entire movements in his imagination before ever setting pen to paper.

He described his creative process in a letter: “I carry my thoughts about with me for a long time… I change many things, discard others, and try again and again until I am satisfied.” For Beethoven, composition was as much a mental and emotional journey as a physical act of writing. He would visualize the architecture of a symphony, test out musical ideas in his mind, and only commit them to paper when he was convinced of their power and coherence.

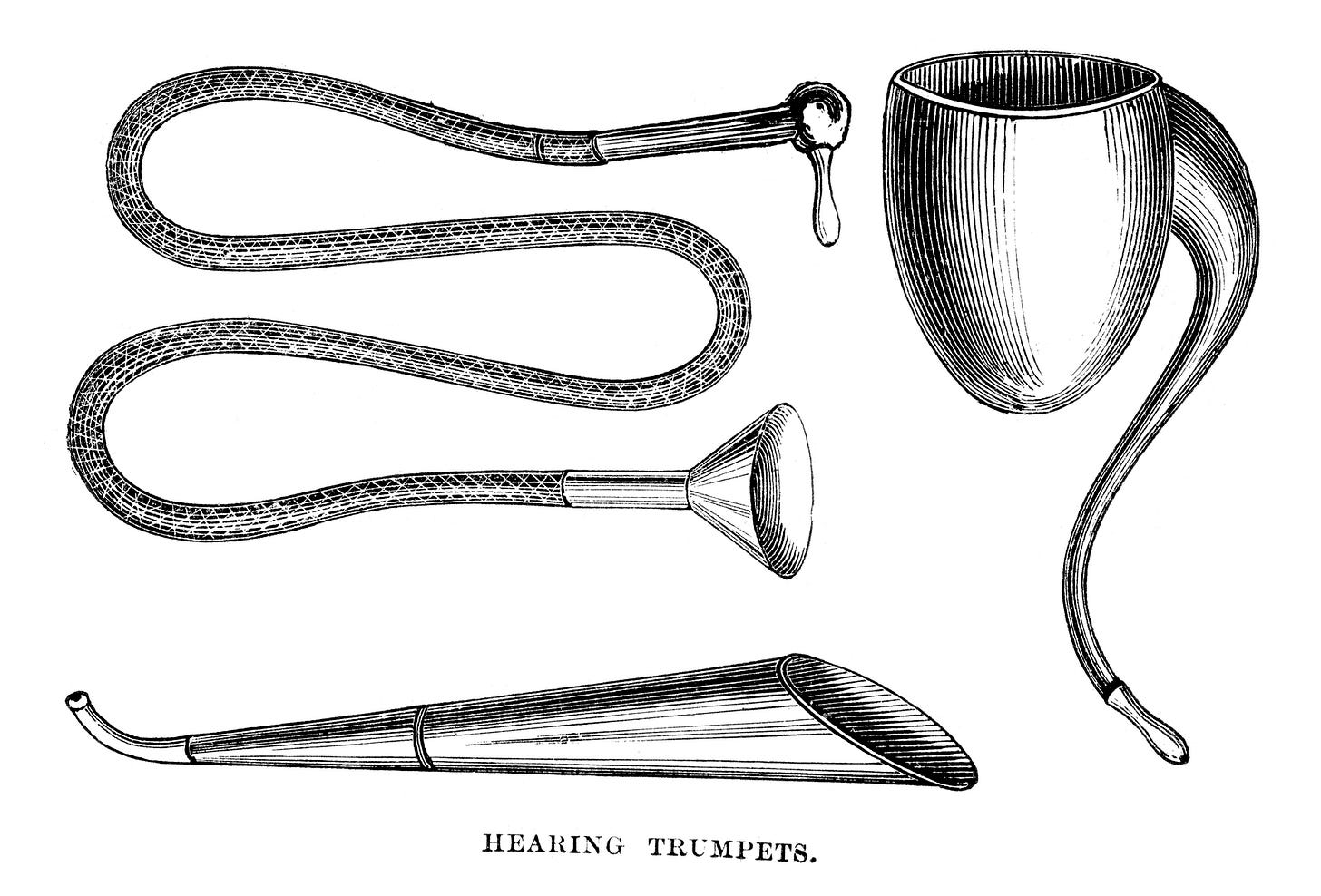

But Beethoven’s ingenuity didn’t stop at inner hearing. As his deafness worsened, he turned to a range of tools and techniques to bridge the gap between his mind and the outside world. He used ear trumpets, one of the primitive hearing aids of his era, to capture whatever fragments of sound he could. His sketchbooks became essential companions, overflowing with musical ideas, thematic fragments, and painstaking revisions. Beethoven often worked out complex passages over many pages, refining and reworking them until they matched the music he heard in his mind.

Communication, too, became a creative adaptation. In his later years, Beethoven relied on “conversation books,” in which friends and visitors would write their questions or comments, and he would respond verbally or in writing. This allowed him to maintain his social and professional connections, even as silence enveloped his daily life.

Perhaps most remarkably, Beethoven developed a tactile connection to his music. He would sometimes place a wooden stick or rod between his teeth and rest it on the soundboard of his piano, allowing him to feel the vibrations of the instrument through his jawbone. This ingenious method helped him judge the dynamics, articulation, and resonance of his compositions, compensating for what his ears could no longer provide.

Through a combination of inner hearing, relentless practice, adaptive tools, and sheer determination, Beethoven transcended the barriers of deafness. His creative process became a testament to human resilience; the triumph of imagination and intellect over physical limitation.

Deafness as a Creative Catalyst

Beethoven’s journey through deafness unfolded alongside three distinct compositional periods, each defined by bold innovation:

Middle Period (1803–1814): As his hearing diminished, Beethoven embraced dramatic contrasts, powerful rhythms, and a greater emphasis on lower registers. Masterpieces like the Eroica and Fifth Symphony shattered Classical conventions, channeling a spirit of defiance and emotional intensity that set a new standard for symphonic music.

Late Period (1815–1827): By this time completely deaf, Beethoven turned inward, creating some of the most profound and radical works in Western music. The Ninth Symphony (1824), with its groundbreaking choral finale setting Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” redefined what a symphony could be. His late string quartets, such as Op. 131, ventured into fragmented textures and spiritual depth, mystifying his contemporaries but profoundly influencing future composers like Stravinsky.

Musicologists have traced practical adaptations in his writing: during his mid-career hearing decline, Beethoven’s scores feature fewer high notes, while in his late works, treble lines return in full force, evidence of a composer now composing entirely through the vivid soundscape of his mind.

Redefining Music and Humanity

Beethoven’s deafness forced him to reimagine the very purpose of music, freeing him from the constraints of auditory feedback and inspiring a focus on emotional truth and structural innovation. His late works, once dismissed as incomprehensible, are now celebrated for their visionary complexity and depth. Through extraordinary artistic courage, Beethoven demonstrated that physical limitations need not stifle creativity; his reliance on inner vision paved the way for future innovators like Schoenberg and Mahler. His triumph over adversity has become a universal symbol of resilience, embodied by the Ninth Symphony, now the anthem of the European Union, which stands for unity and hope. Even today, scientists study Beethoven’s methods to better understand neuroplasticity and how the brain can process and create music in total silence.

Final Thoughts

Beethoven’s deafness did not silence him, it liberated his genius. By transcending the need to hear, he composed music that transcended earthly constraints, offering a glimpse into the boundless potential of the human spirit. As he once declared, “Music is the mediator between the spiritual and the sensual life.” In his silence, Beethoven found a voice that echoes eternally.

Opus Picks: Recommended Recordings

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 (“Choral”): Beethoven’s triumphant final symphony, renowned for its groundbreaking choral finale and powerful message of unity.

String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131: A deeply introspective and innovative masterpiece from his late period, admired for its emotional depth and structural daring.

Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major, Op. 106 (“Hammerklavier”): One of Beethoven’s most ambitious and technically challenging piano works, showcasing his visionary approach to form and expression.